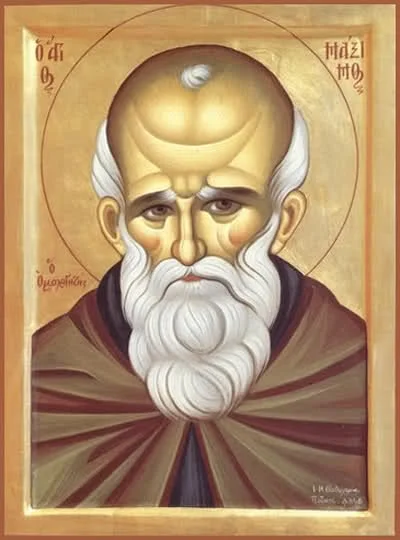

The Mystery of the Three Flames of St. Maximus: “Tamar and the Trinity”

This story comes to us from the Tsekuri Mountains in the country of Georgia, where an old military fortress towered over local villages. Set in the 7th century AD, this scene of fantastical biography invites you to look at a controversial time in church history through the eyes of a child.

Tamar walked behind Bebia on the path to the cemetery. Even though she was a big girl of nine, she dragged her feet. At the edge of the village, they were joined by a short, bent-over shoemaker who hobbled along with them. As they started down the hill, she saw two monks in long dark robes walking ahead of them. They were the two young men who had traveled with the prisoner the soldiers dumped in the fortress.

Holy is what her grandmother Bebia called the prisoner, but as far as Tamar could see, he was just a frail and sick old man.

She wasn’t surprised when he died, but she was surprised when the local clergy refused to serve the funeral service. Something to do with a heresy about the Trinity. Instead of a proper service, the two monks read a lay version of it. Tamar was there because Bebia dragged her to watch the monks put their old Abba in the ground. They waited in the rain with a dozen or so other peasants. Several other grandmothers stood back like stones along the wall, squatty round ladies with green or blue handkerchiefs on their heads. Tiny lines of water dripped down their faces and they made the sign of the cross over themselves.

Now it was three days later.

The young monks pushed the gate open, and Tamar and the villagers followed them past the tidy graves. Each grave was covered with a flower bed lined with white rocks.

But that’s not where Abba Maximus was.

The little procession passed the beautiful beds and turned towards the back corner, covered in weeds and thorns.

Tamar huffed and frowned at the ugly mess of vines, but Bebia kept walking forward with the other peasants, dragging Tamar with her.

They rounded a corner, but before she could see the tomb, Tamar heard the sharp intake of air from the shoemaker. All around her, grandmothers released similar gasps and short “oh’s!” and even long, low “ooooooos.” The youngest children cheered, and her Bebia whispered, O, Lord Jesus. Tamar ducked down and squeezed between musty coats and dark brown work pants, making her way to the front of the crowd so she could see what was causing all the fuss.

She stared at the grave of the prisoner.

Above the mound of dirt, three flames burned.

No wicks, no candles, no oil lamps.

Just three flames hovering in the air above the humble dirt.

Three, just like the Trinity.

Tamar gripped Bebia’s hand tightly. Bebia reached over and patted her hand and whispered. “You are witnessing a miracle, my little dove.”

They stood completely still and stared at the flickering flames. Tamar felt small compared to the miracle, but big because she got to be there. Even her chest felt glowing from the flames.

A few minutes later, heavy footsteps broke the peaceful moment. Tamar turned to see black guards’ boots splashing towards them.

One of them shouted at Tamar and the others. “Who tampered with the grave?”

She winced and stepped back. Could he see the flames?

The other guards stopped, looking at the grave in reverent surprise.

The loud one ran away, calling for help, but the remaining guards dropped to their knees and bowed at the sight of the three burning flames.

After that, Tamar and Bebia made the little walk to the cemetery every day. Over the next few weeks, pilgrims from up and down the mountain joined them, and the local clergy finally began to pray a daily memorial.

The young monks cleaned up the weeds around the grave and put white stones around its perimeter. The youngest one, George, asked Tamar if she would maintain it when they left. She nodded her head solemnly, eyes big at the thought of that important, grown-up job.

That afternoon, George carefully showed her how to add more oil and trim the wick. Every evening, she went to tend the little glass lamp, and every evening, she found new posies of flowers lining the grave.

Tamar enjoyed the serious and solemn and beautiful job of tending Abba Maximus’ grave. Eventually, the village saved up enough money to have a stone carver engrave a headstone. It read:

Maximus, the Confessor, Defender of the Light of the Trinity

Bebia was right. He must have been holy.

Even after years and years, when Tamar herself had become a Bebia, her stomach felt butterflies each time she trimmed the wick and added oil to the lamp at the grave of Abba Maximus, for she remembered the three flames.

Lagniappe

In Louisiana, we use the Creole French word Lagniappe (lan-yap) to mean "a little something extra."

1. On the liturgical calendar, St. Maximus the Confessor is remembered January 21, as well as August 13.

2. Why does he have the title, "The Confessor?" This designates that although he was not killed for Christ as a martyr, he suffered for the sake of his Savior. A prolific teacher, his enemies cut out his tongue to quiet him. This didn't stop him - he could still write! So they cut off his fingers, before sending him into exile.

3. The miracle of the three flames is straight from his biography, and some of his disciples did travel with him into exile, but I invented Tamara so I could tell the story from the eyes of a child.

Would you like to receive stories like this every month? Sign up for my newsletter (which I affectionately call my Storyletter) by clicking on the link at the top of the page.